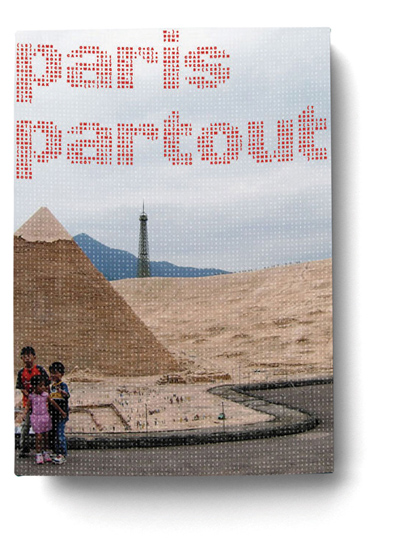

Paris Partout

short description

Photographs by Jenny 8 del Corte Hirschfeld

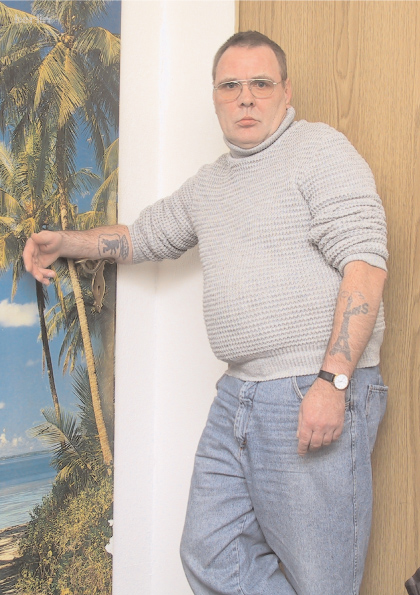

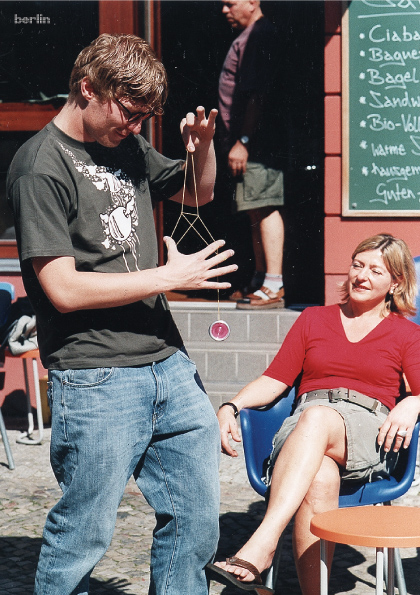

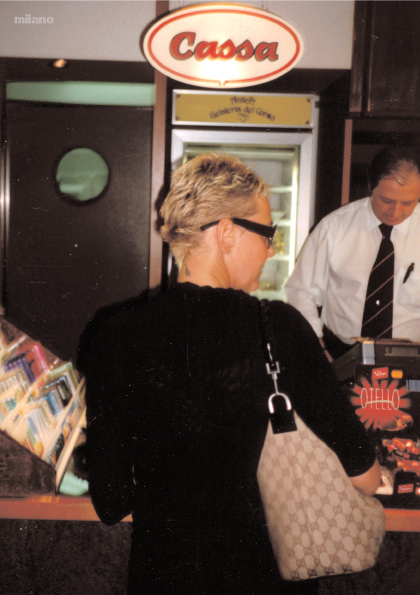

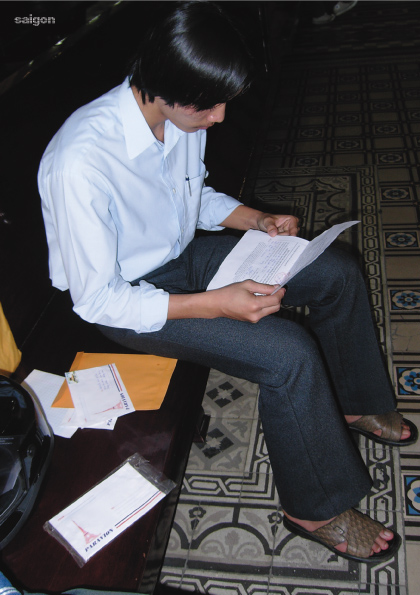

Stroll through any of the world's major cities, through suburban towns and rural

villages-whether in New York, Mombasa, or Wolfenbuettel -and you will discover

Eitfel towers integrated into even the remotest corners of daily life, As a truly

global icon, the Eiffel Tower has come to signify much more than France, or

even Europe; it promises something marvelous, some intangible fantasy the

embodiment of some abstract desire. What is it about this particular structure

that it has captured the imagmation of people all over the world? that it compels

us to stamp its emblem on so many facets of our lives? We affix towers to our

company logos and our storefronts to our clothing and jewelry to our food and

even our bodies. Applying its particular lens to bustling streets around the globe.

Paris Partout explores the strange and familiar contexts in which these images

appear, capturing in snapshots the fleeting moments of an Eiffel Tower world.

Through a conceptual constellation of Eiffel Tower images from around the

world Paris Partout provides the reader with a unique perspective on cultural

spaces and the people who inhabit them.

DREAMLANDS

Paris Partout

at Centre Pompidou

Dreamlands

5. Mai bis 9. August 2010

Centre Pompidou, Paris Frankreich

GALERIE 1,

Gruppenausstellung

Teilnehmer:

Artists

Al Ghaith Reem,

Andrea Robbins and Max Becher,

Arbuckle Roscoe,

Arbus Diane,

Archigram,

Attia Kader,

Bacon Lloyd,

Barbieri Olivio,

Berdaguer & Péjus, Bernado

Jordi, Bourgadier Hermine,

Bruce High Quality Foundation,

Buckminster Fuller Richard,

Cam Emilie & Ferrand Rémy,

Cantor Mircea,

Cattelan Maurizio,

Chancel Philippe,

Constant,

Couturier Stéphane,

Dali Salvador,

Dardi Costantino,

Del Corte HirschfeldJenny8,

Depero Fortunato,

Desouza Allan,

Farrell Malachi,

Féau Théophile,

Fullerton-Batten Julia,

Ghirri Luigi,

Gordon Smith,

Graves Allan,

Grasso Laurent,

Gursky Andreas,

Guston Philip

Hollein Hans,

Huyghe Pierre,

Joye Florian,

Kelley Mike,

Kingelez Bodys Isek,

Koolhaas Rem,

Kwong Chi Tseng,

Leirner Nelson,

Leve Edouard,

Mogarra Joachim,

Moholy-Nagy Laszlo,

Montes Fernando,

Pablo Picasso,

Parr Martin,

Pesce Gaetano,

Podsadecki Kazimierz,

Power Thomas,

Price Cedric,

Purini Franco,

Riedler Reiner,

Rogers Richard -,

Piano Renzo,

Rossi Aldo,

Ruscha Edward,

Savinio Alberto,

Schaal Eric,

Scolari Massimo,

Sottsass Ettore,

Sriwanishpoom Manit,

Stella Joseph,

Struth Thomas,

Superstudio,

Timtschenko Alexander,

Venturi Robert Studio,

Vriesendorp Madelon,

Woo Back Seung,

Wei Liu,

Weinberger Thomas,

Xiuzhen Yin,

Zangkhe Jia

Multidisziplinaere Ausstellung mit mehr als 300 Werken, moderner und contemporaere

Kunst, Architektur, Film

PARISTICHE

by Paul Stephens

The text is a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centers of culture.

—Roland Barthes

“Here we are all citizens of the Eiffel Tower,” proclaimed one speaker at the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle, where the newly-constructed Eiffel Tower stood straddling the main entrance. The Tower symbolized the triumph of the French Revolution, of the Third Republic, of the industrial age—above all it symbolized France’s vitality as a nation and France’s power as an empire. No European nation has come to be associated so singularly and so widely with one monument. The Tower stands for the crassest aspects of a global culture of tourism—reducing Frenchness to something easily understandable in the same way as the beret, the baguette, and Pepe le Pew. But the Tower represents much more than Frenchness or the culture of tourism or the culture of mass-produced romance. The Tower has become the proliferation of its own images. The empire has been writing back to the metropole about its grandest, most non-utilitarian symbol for more than a century now. The Tower’s ubiquitous image is a kind of shorthand for the difficulties and the beauties of globalization. The Tower, as this book shows, is not just a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centers of culture, it is a tissue of images drawn from the innumerable centers of culture.

Like the Exposition it accompanied, the Tower was built to proclaim that the world belonged to Paris, but it soon became apparent that Paris also belonged to the world—and too much so for the liking of some Parisians. The “presence at the fair of thousands of natives from the colonies worried self-appointed monitors of public morality. A correspondent from one very proper Paris newspaper wrote, ‘I must demand supervision of these natives whose loose morals border on licentiousness. It appears that their behavior is due to an excess of innocence on their part. But they would be just as interesting if they were a little less innocent.’” The natives would not, of course, be just as interesting if they were “less innocent.” A world exposition is meant to display the exotic, the threatening, the new. It was, in fact, the more ambitious developing nations that built the grandest pavilions at the Exposition. The great European monarchies were threatened by the Exposition and by the Tower. Britain and Germany saw a resurgent France which had recovered from its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, and they saw a Republican France which had confidently buried the ghosts of the Paris Commune. Neither the British nor the Germans contributed to the fair on the national level. While the United States government contributed a paltry amount to its exhibition, the countries of South and Central America spent lavishly, seeing Paris as the most natural place in the world to advertise their coming of age. Mexico built the grandest pavilion at the Exposition; Argentina followed close behind. Bolivia, Nicaragua, Chile, San Salvador, and Santo Domingo all had buildings of their own.

Even in 1889, the world was already in the shadow of the Tower. From the beginning the Tower aroused controversy. The Tower was too modern, too overwhelming, too frivolous, even too cosmopolitan. The Tower was the grandest monument of the Belle Epoque—it stood on the cusp of modernity, the tallest building in the world. It preserved elements of the classical in its triumphal arches, but it was absolutely modern in its use of the most advanced methods and materials. Its four corners represent the four corners of the world; the height of its hyper-efficient pointed phallus proclaims a desire to transcend the limits of the world. Guillaume Apollinaire’s poem in the shape of the Tower begins with the words “Salut Monde.”

The poem begins by welcoming the world; it ends by turning the poem and the Tower into a giant French fuck you aimed at the Germans. Writing on the front lines in World War I, Apollinaire could invoke the Tower’s universalism at the same time he could snub the traditional enemy. The Tower has always been an unambiguous symbol of nationalism and an ambivalent symbol of internationalism.

In his essay on the Tower, Roland Barthes retells the famous story of Maupassant’s dining at the Tower simply so that he could escape from its omnipresence as a Parisian landmark. “It’s true,” Barthes writes, “that you must take endless precautions, in Paris, not to see the Eiffel Tower.” Paris Partout demonstrates that it’s also true that endless precautions are necessary not to see the Eiffel Tower anywhere you go in the world. The Tower, according to Barthes, “belongs to the universal language of travel.” The tower is universally recognizable, as the designers of the Exposition Universelle surely wished, but the Tower’s ubiquity generates many meanings in many contexts. The Tower may be “a universal cipher,” as Barthes suggests, but a cipher is still a cipher—it needs to be decoded. As a cipher, the Tower marks both the gains and the losses involved in the cultural syncretism of an increasingly small world. How those gains and losses are deciphered will depend on one’s subject position in the global marketplace of ideas, images, and bodies.

If the Tower epitomizes the global traffic in images, it nonetheless stands resolutely opposed to the domination of that traffic by Americans in the twentieth century. One of the most serious charges leveled against the Tower by the signatories of the manifesto condemning it was that not even “commercial America” [commerciale Amérique] would tolerate such an inhuman mechanistic design. In a sense, the Tower’s critics were right. America would always be too utilitarian for a project like the Tower. America’s tall buildings would enclose offices, not empty space.

Within the modern culture of the spectacle, the Tower benefited immediately from the controversy it generated. A number of prominent artists including Maupassant and Dumas signed the manifesto condemning the Tower. Writing to a fellow government minister who was wondering how to react to the anti-Tower manifesto, Edward Lockroy, who was in charge of plans for the Exposition Universelle of 1889, wrote: “What I pray you to do is to accept the protest and to keep it. It should be placed in a showcase at the Exposition. Such beautiful and noble prose cannot but interest the crowds, and perhaps even amaze them.” Nostalgic aestheticism could not slow progress. There could be no such thing as bad publicity in the new age. One’s attitude toward the tower was a direct reflection of one’s attitude toward modernity. Gertrude Stein, for instance, in her book Paris, France, takes the Eiffel Tower as a prime symbol of modernity and of its characteristic rootlessness:

Alice Toklas said, my grandmother’s cousin’s wife told me that her daughter had married the son of the engineer who had built the Eiffel Tower and his name was not Eiffel.

When were having a book printed in France we complained about the bad alignment. Ah they explained that is because they use machines now, machines are bound to be inaccurate, they have not the intelligence of human beings, naturally the human mind corrects the faults of the hand but a machine of course there are errors. The reason why all of us naturally began to live in France is because France has scientific methods, machines and electricity, but does not really believe that these things have anything to do with the real business of living. Life is tradition and human nature.

And so in the beginning of the twentieth century when a new way had to be found naturally they needed France.

America and France, as Stein was fond of remarking, were really the only two modern countries. The difference between America and France was that the Americans constantly wanted science and technology to change “the real business of living.” The French, by contrast, were even more modern because the French did not need to instrumentalize their inventions. Americans might believe that machines could eventually replace humans; the French would never believe so. In the beginning of the twentieth century, when a new way of life was needed, naturally the Eiffel Tower served as an ideal model. Life could be “tradition and human nature” at the same time that it could be absolutely modern, transcending tradition and human nature.

As Stein and other modernists understood, the Tower is a symbol of global simultaneity. At 10 o’clock on July 1, 1913, the first time signal transmitted around the world was sent from the Tower. World Standard Time had been born. Like so much else in the arrangement of global affairs, the nature of World Standard Time was dictated by France and England. The historian Richard Kern notes that “If the zero meridian was to be located on English soil, at least the institution of world time would take place in France.” To make up for the symbolic loss to Greenwich, Paris hosted the International Conference on Time in 1912; thenceforth even the shape of time was imposed by the great Imperial powers. In the same year that World Standard Time was born from the Tower, Blaise Cendrars monumentalized the Tower in his poem The Prose of the Trans-Siberian. 150 copies of the poem were to be printed; each copy would be two meters long. Collectively the poems would be 300 meters long, equaling the height of the Tower. In the lower left hand corner of the poem is a small Tower. The poem concludes by brilliantly locating itself in “Paris: Ville de la Tour unique du grand Gibet et de la Roue.” “Paris: City of the Incomparable Tower the great Gibbet and the Wheel.” The incomparable Tower can only be compared to two torture devices. The modern individual can be hung from the linear gallows or stretched on the semi-circular wheels at the base of the Tower. Perhaps we are to enjoy being tortured by the most beautiful and complex of torture devices. In any case, there is no escape.

Like the French nation in general, the Tower is a marvel of efficient inefficiency. The Tower is the perfect symbol of an empire that was never quite as stable and as inexorable as its British and American counterparts. The Tower offers something of a reminder of the hubris of advanced European societies; it is an audacious industrial monument within a society that was not able to industrialize as rapidly as its counterparts. The Tower’s universalism resides in its commitment to the ideals of progress, and yet the Tower has become an icon of nostalgia. It advertises its own inclusiveness, much like the intensely centralized administration of the French Empire. Colonial subjects were to become French and partake in the culture of Paris to a far greater degree than their British counterparts were to partake in the culture of London. The universal ideals of the empire were, of course, never as universal in practice as they were in theory. Toussaint L’Ouverture and Napoleon both equally invoked the Rights of Man. As it turned out, the Rights of Man did not apply to slaves.

The signatories of anti-Tower manifesto also claimed to appeal to the universal, even if they claimed they were but a “...to be but feeble echoes of universal opinion.” They suggested that “...when foreigners would come to visit our Exhibition, they would be likely to exclaim in astonishment “What! Is that horrid thing the only thing that France has managed to come up with in order to give us insight into their supposedly exquisite taste?” In the end, foreigners were not horrified but captivated by the Tower. The opposition of nineteenth century French Academic painters and architects was not even a feeble echo of universal opinion. Empires captivate their subjects by many means.

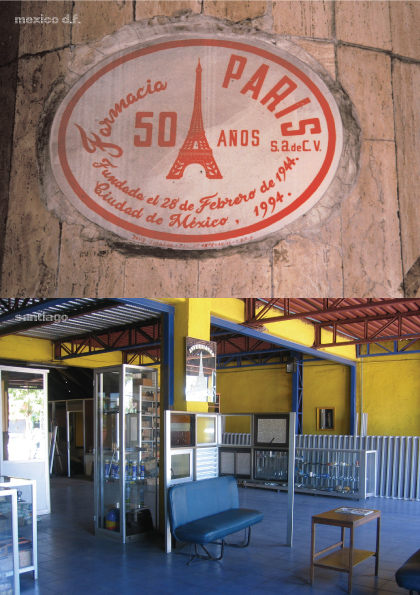

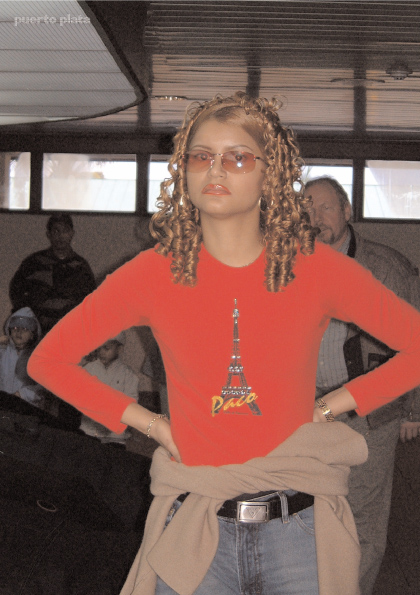

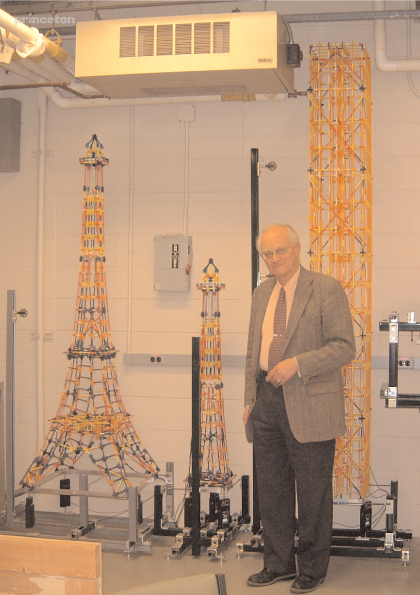

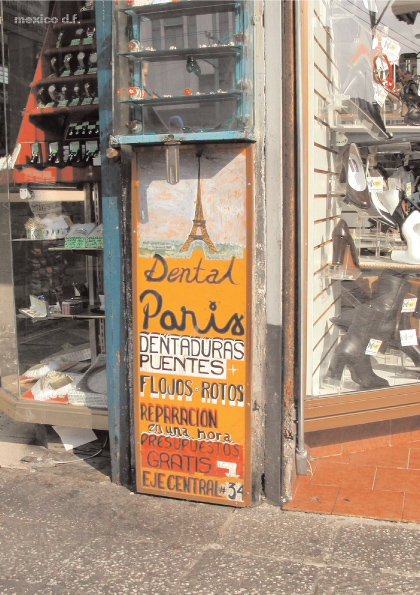

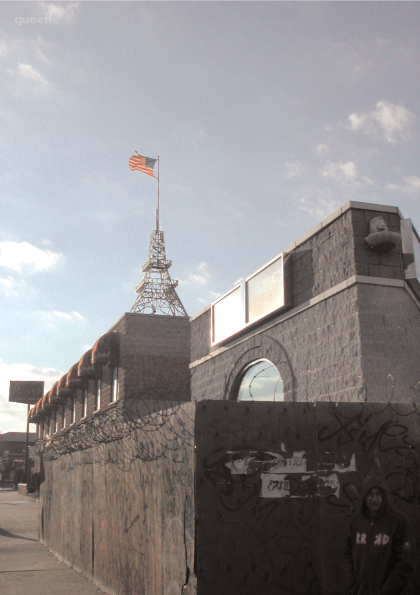

Given that all of the photos in this book adhere to one simple constraint, they capture a remarkable variety of scenes, characters, and interactions. Despite their immense geographical range, the pictures do share a number of tendencies. The Tower is almost always a symbol of familiarity, a symbol of welcome. In a majority of photos the Tower is used as a marketing logo. The Tower’s image (alas) has been trademarked by the semi-private company which runs the Tower. Nonetheless, the Tower’s image (or more accurately its images) will always belong to everyone, so long as you can buy or produce a copy. In one of my favorite photos, a well-fed woman waits outside Grand Central Station in New York City, carrying (or rolling) a Las Vegas bag. Given that Las Vegas has its own simulacra of a Grand Central Station and of an Eiffel Tower, the picture could just as easily have been taken in Las Vegas. The destinations are interchangeable. In Kosagoe, the Tower gets a boost in scale as it dwarfs a World Trade Center, an Empire State Building, and a Chrysler Building. Americanization might be inevitable, but it can be resisted in innumerable small ways.

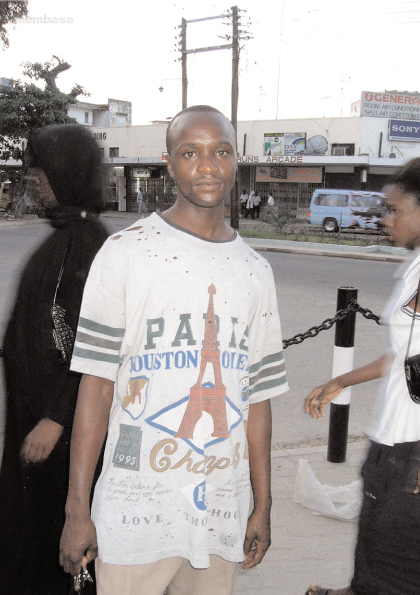

A utopian theme park urge to shrink the world animates many of these photos. At the same time, a uniform commercial shabbiness haunts them. Take, for instance, the photo of a man in Mombasa who wears a cast off shirt from a Texas oil refinery. The shirt is moth-eaten and dirty and yet its owner appears proud, a set of keys in his hand. Used American t-shirts are a prized commodity in many parts of Africa. Perhaps the Tower’s symbolic value increases as one’s likelihood of ever seeing it decreases, just as a used shirt acquires a new value when it is transported to another continent. The Tower is infinitely adaptable, infinitely transportable. In Paris, Texas, it wears a cowboy hat. In Dalat, it serves as a lamppost which holds cabbage pots. In Odessa, it serves as a stand for a Christian Dior poster. In Switzerland, it holds up a picnic table; one can indeed dine within the Tower even when one is not in Paris. Businesses around the world with pretensions to Frenchness use the Tower as an instantly recognizable symbol of authenticity. If the Tower has inspired great creativity, it has also induced extraordinary homogeneity.

Above all perhaps, Paris Partout shows that the world is a pastiche of Paris, and Paris is a pastiche of the world. Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer once wrote that “Humanity has always been more at home in France than anywhere else. But the French themselves were not aware of this.” The twentieth century showed that Paris will always be only one of the innumerable centers of culture. Paris is the birthplace of photography, of the collage, of the pastiche, and of the cultural syncretism that gave birth to modernism and the avant-garde. These are Paris’ gifts to the world, but Paris owes the world more than it can ever repay. In terms of blood and labor and ideas, Paris has taken much from the world. Paris during the twentieth century was, more so than any other city, that curiously oxymoronic place, the “expatriate’s home.” In many senses, the entire globe is becoming an infinite complex of expatriate’s homes. The Eiffel Tower may be a symbol of hope and cultural exchange, but the Tower is also a symbol of the immobility and poverty of the majority of the world’s peoples. The dispossessed of the world fetishize the Tower’s image in part because they will only ever dream of seeing it in person. In 1999, a UNESCO Manifesto for World Peace was launched at the Tower. More than seventy-five million people have signed this simple document. Whatever effect such a manifesto might have, it speaks to the continuing role of the Eiffel Tower as a symbol of something reassuringly morethan French and something painfully less than universal.

1 Roland Barthes, The Eiffel Tower and Other Mythologies, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1979), 4. 2 Gertrude Stein, Paris France: Personal Recollections (London: Peter Owen, 1971), 8. 3 Stephen Kern, The Culture of Time and Space 1880-1918 (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1983), 13. 4 Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, The Dialectic of Enlightenment, trans. John Cumming (New York: Continuum), 225.

© Urheberrecht. all rights reserved

Wir benötigen Ihre Zustimmung zum Laden der Übersetzungen

Wir nutzen einen Drittanbieter-Service, um den Inhalt der Website zu übersetzen, der möglicherweise Daten über Ihre Aktivitäten sammelt. Bitte überprüfen Sie die Details in der Datenschutzerklärung und akzeptieren Sie den Dienst, um die Übersetzungen zu sehen.